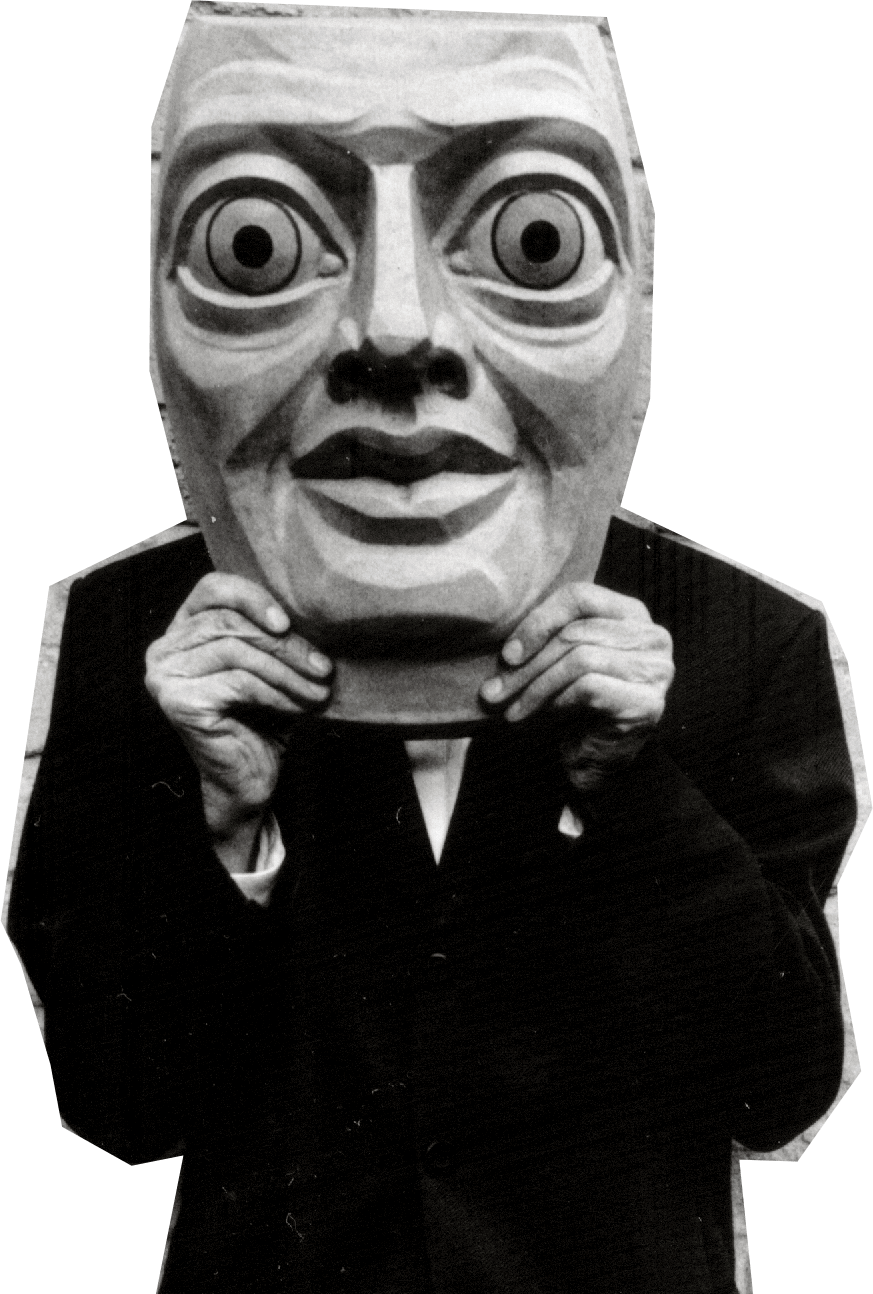

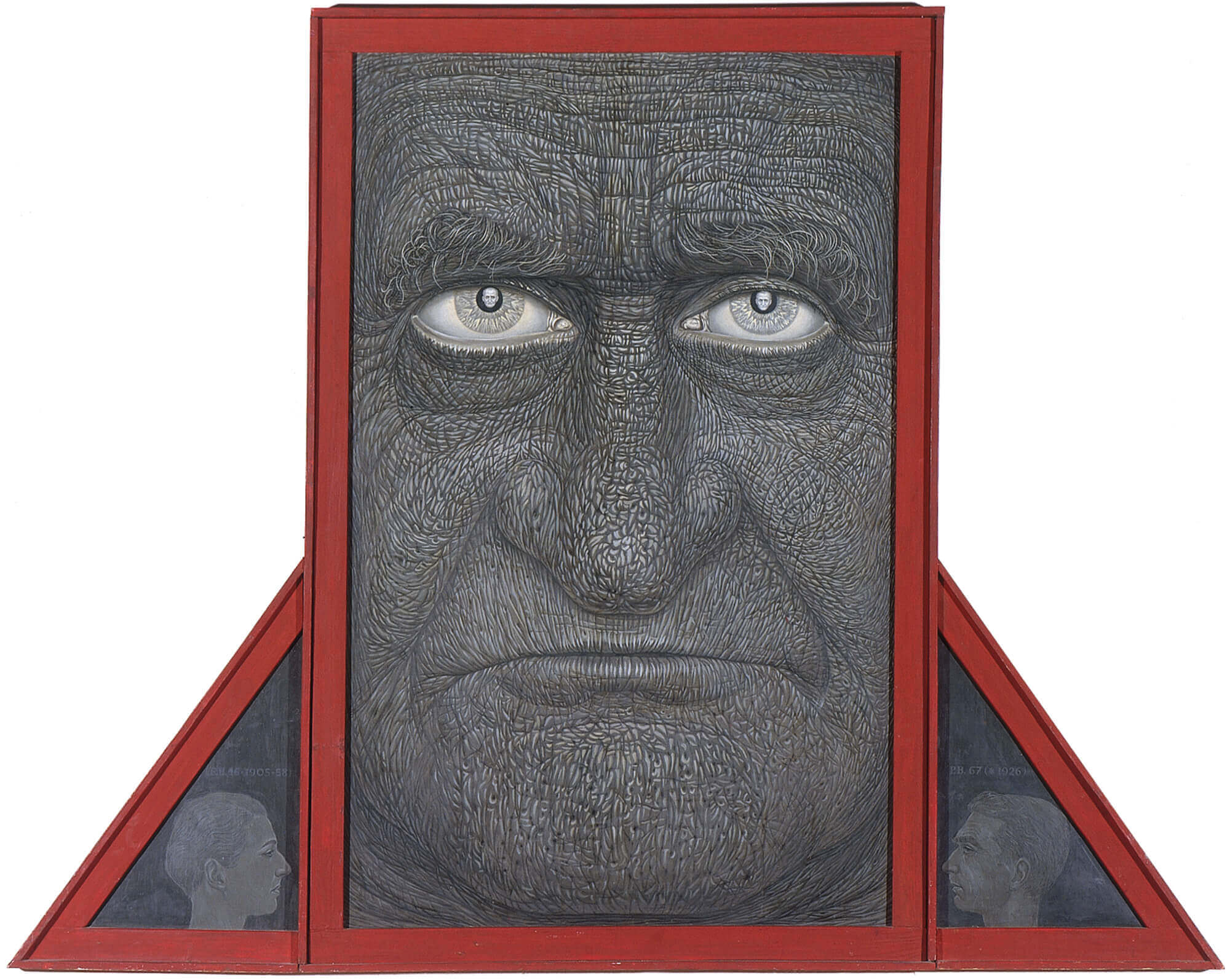

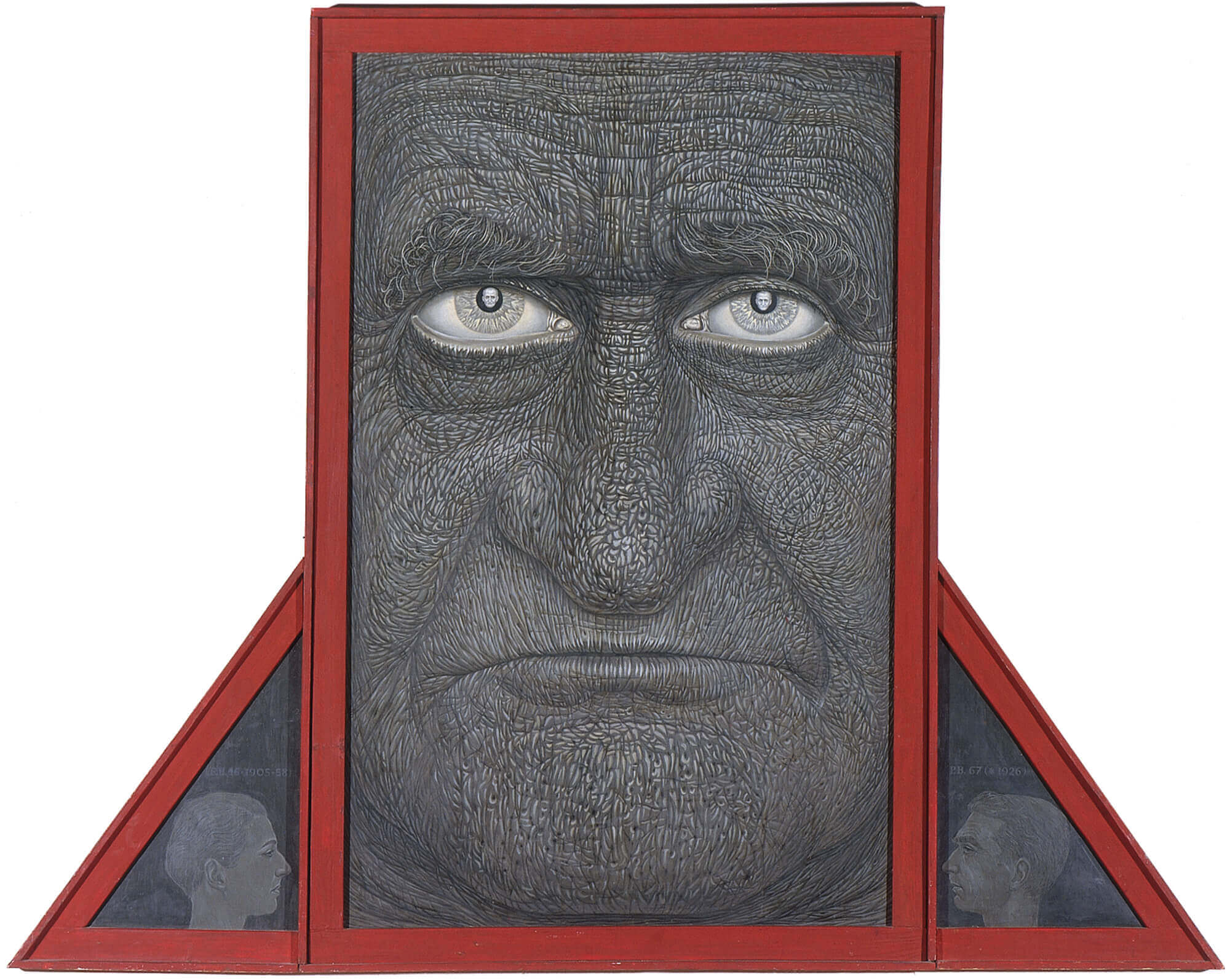

Father's portrait

1967

Father's portrait

1967

This portrait draws from the mutually tense and often conflicted relationship between the author and his model. It is an ironic celebration and humorous revenge for his past injustices and – as it subsequently turned out – future ones as well. The father is presented – and this is how he is generalised – as a self-centred and somewhat intimidating authority, a monumental centre of some three-part altarpiece. The result is a bizarre deity seen from a terrible proximity.

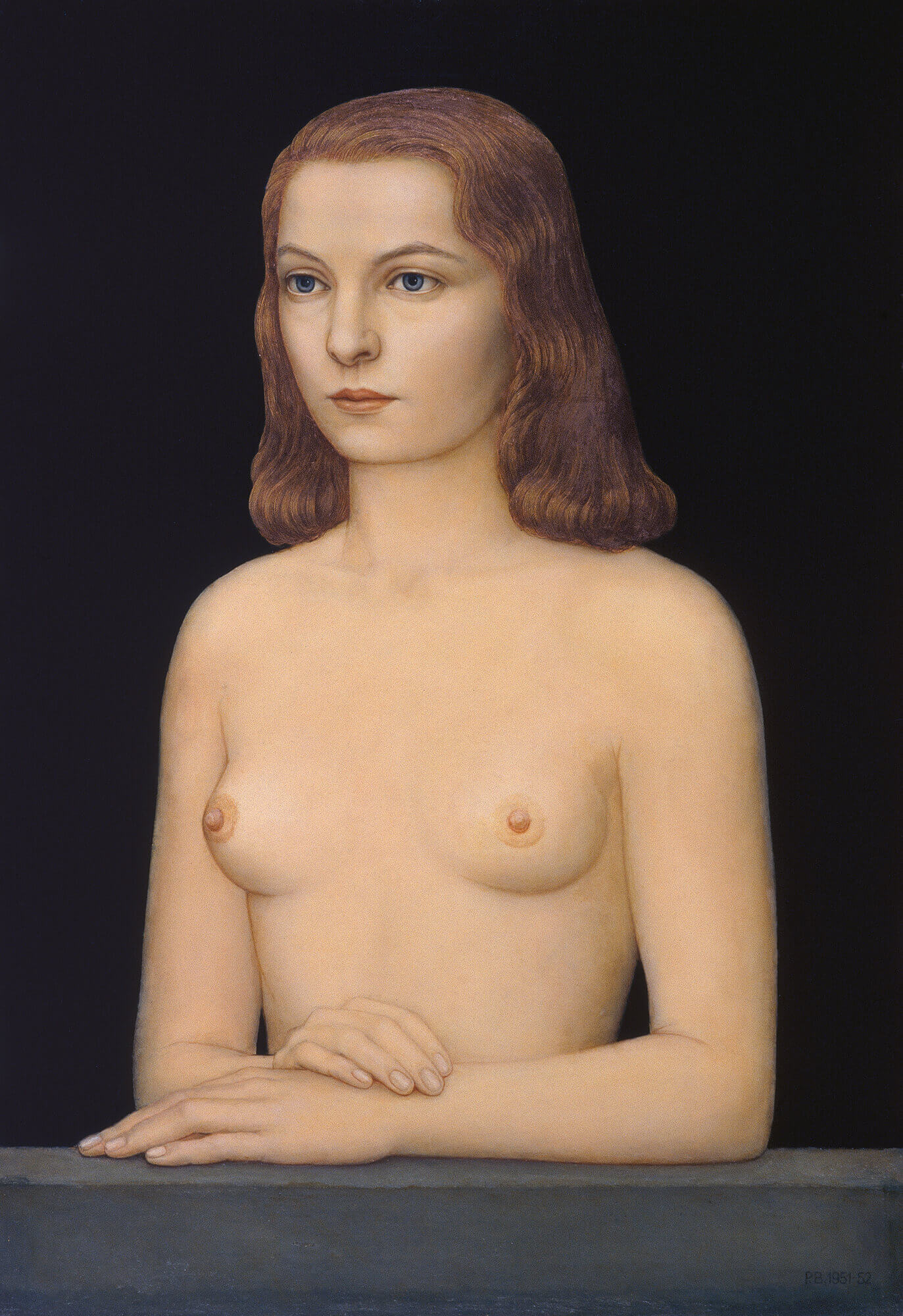

Tender-eyed tenderfoots tend to attend tender loins

second version, 2005

The influence of personal circumstances generally appears with great delay in P.B.’s work. One extraordinary event was a great, spectacular tour of Italy that P.B. and V.N. went on in 1967 for 100 dollars that they had put together.

The amazing delight that P.B. experienced when he saw (beside many other works) Angelico’s paintings in San Marco church in Florence, together with the modest Skira monograph, the only publication featuring good-quality reproductions, made him want to use similarly tender, clear and bright colours. He did so when he coloured the first composition that offered itself. What is happening in the painting – in contrast to the imaginary order of the angelic Master and all other equally admired artist of the duecento, trecento and sometimes quattrocento – is too much like the arbitrary disorderliness of the earthly life to come near the unattainable perfection of their ethereal Beauty. In any case, they are different works of art.

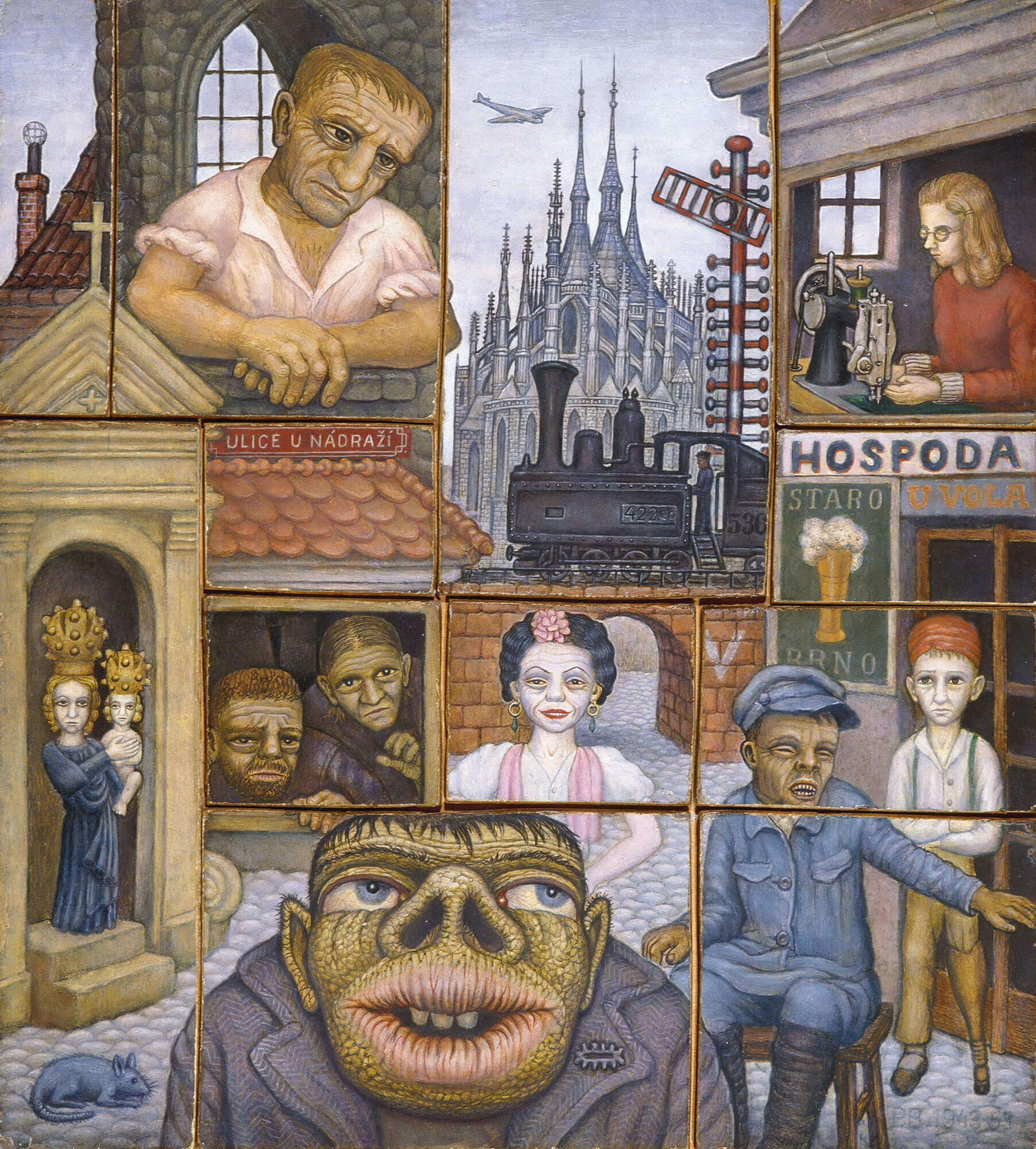

City behind the walls

Late 1970s

City behind the Walls is a splendid, perfect painting, classical and aesthetically pleasing. The subject is more disturbing, though. It is Brázda’s subrealism at its deepest obscurity.

This terrible, extremely psychological work, one of the scariest painted by the artist, its final conception being created by the notorious evil nymph Anna Lisa, represents an infernal, or infernal-seeming forbidden land behind normal world and beyond its control. Secret ritual scenes are enfolding in the painting, the parables of which reveal the true nature of bizarre relationships and their accompanying complexes.

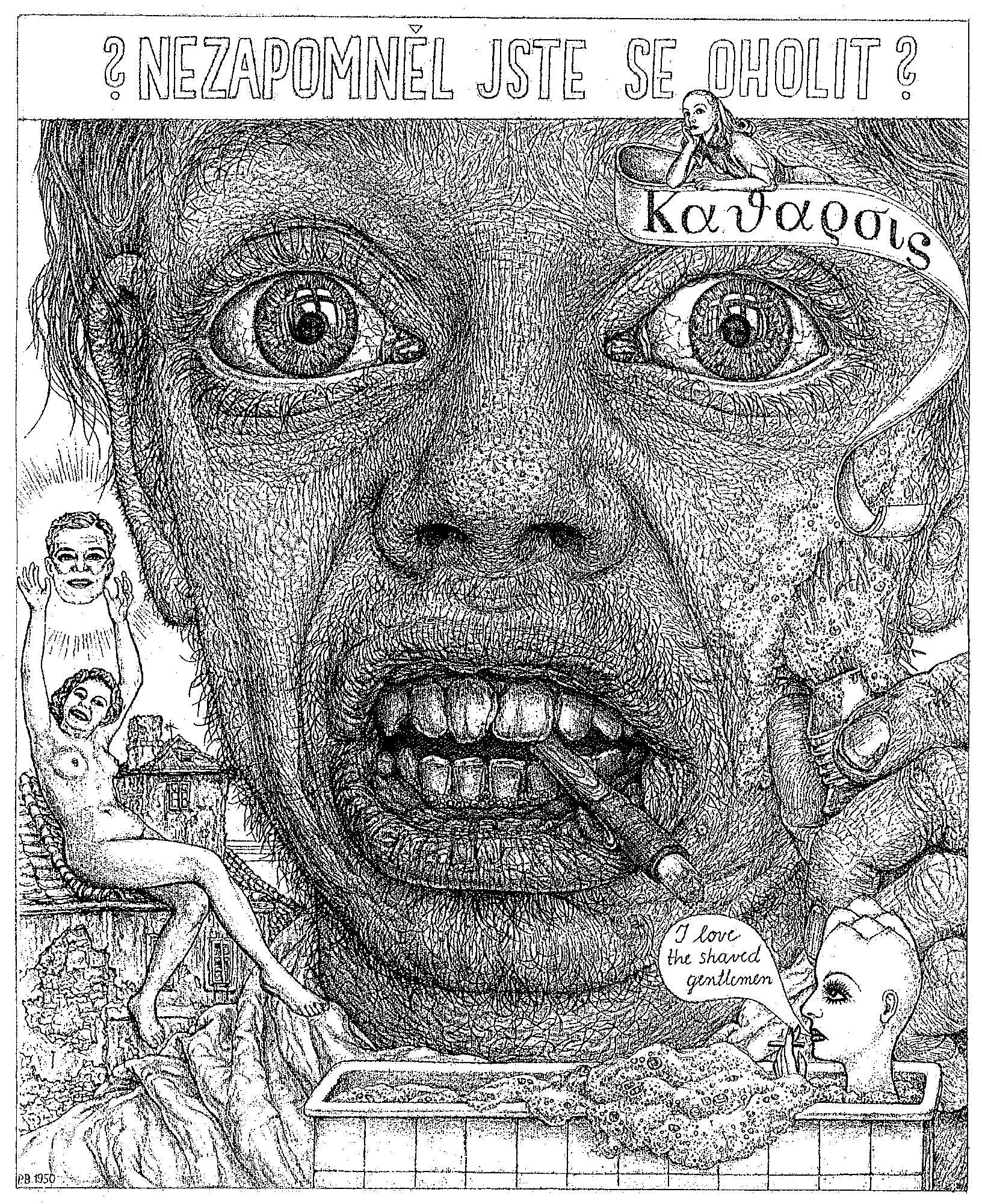

Trial

late 1970s

Trial

late 1970s

This painting is above all a monument to the communist totalitarian system, and by extension, to all similar police regimes from inquisition to present-day torture chambers. It depicts political monster processes of 1950s, primarily with Milada Horáková, Záviš Kalandra and others, and their permanent marks in the following years of the resulting regime.

The theme began to emerge unintentionally. First, P.B. was intrigued by a reproduction of a film poster of I, THE JURY, published in a regular Czech newspaper, which was a rare exotic document the like of which he collected. The poster presented a super-tough hero, apparently purely brutal, an American secret agent James Bond shooting a bare-breasted woman in the belly.

The captivating words I, THE JURY then resonated in the head of the future maker of this work. It reminded him of the judge from I, the Jury, who sent the opponents of a terrorist system to death and of the methods that were used to press the victims. Just hearing the broadcasted testimonies, in which these once free normal people accused themselves speaking in phrases inserted in them like into machines was an unforgettably dreadful experience. It was an open demonstration of the skills of Soviet people-breaking experts, who could transform humans into perfectly manipulated creatures, and the work of their local colleagues.

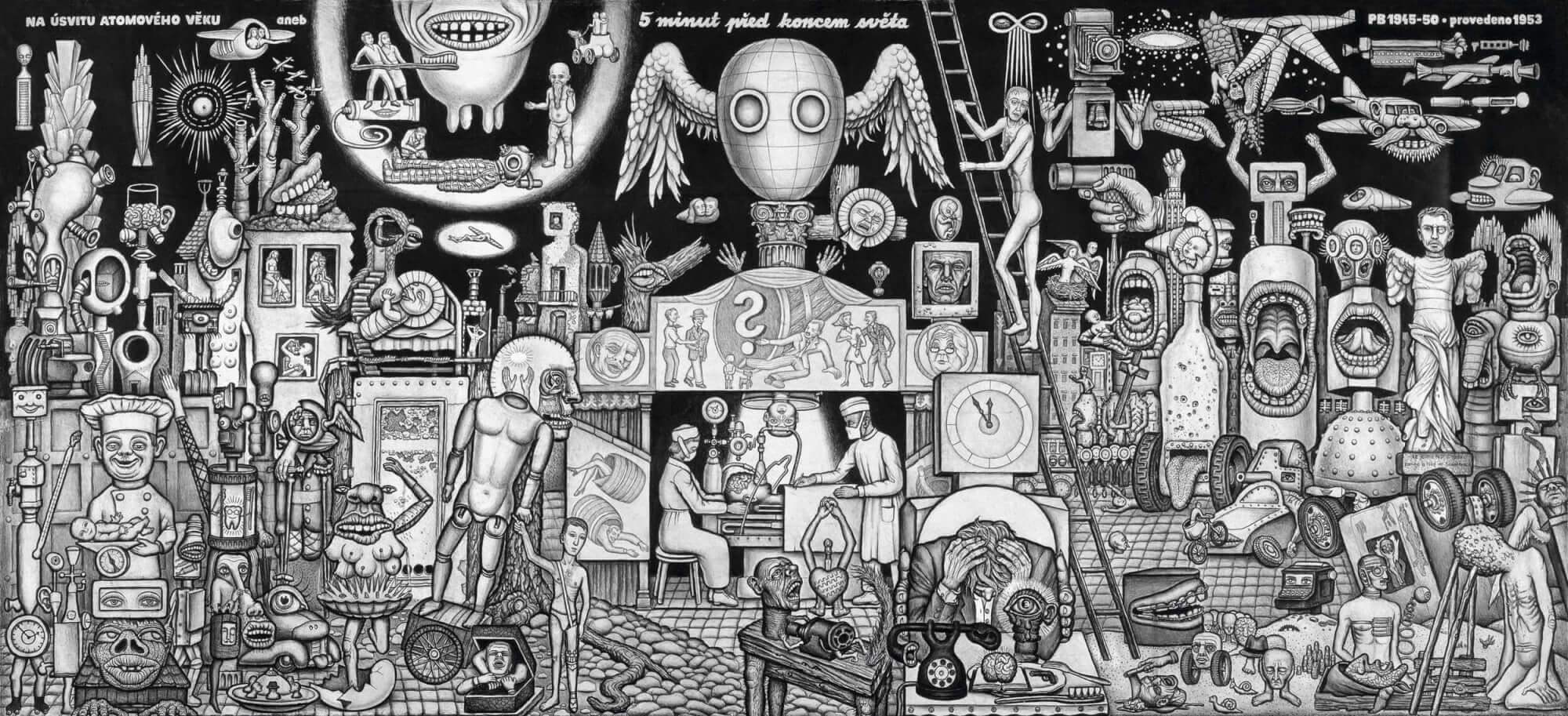

Frank the frank appearing larger-than-life

1970s

Frank the frank appearing larger-than-life

1970s

In early 1970s, PB met an old mason, Mr Stehlík, whom he helped with work on his family country home in Rumburk, and who was expert in stucco plastering. Brázda learnt to cast plaster from him. He began with a series of embossed faces. He made use of children’s plasticene; on a glass pad he moulded embossed heads or masks or faces, to be more exact. He based them on classical models, especially ancient ones from Mesopotamia, Egypt and ancient Greece.

Thus instructed, only exceptionally taking notice of the real model, Brázda stylized these faces into several inconspicuously different types in a deliberately moderate and classical manner; very differently from his oneiric faces from the same period.

PB especially concentrated on polychromy. He used aluminium and bronze, combined with various acrylic paints. To enliven the coloured areas, he sometimes sprayed them with a fixing tube. He put special emphasis on eyes, which usually were a different colour. They stand out even more distinctly like coloured enamel inlaid into ancient, originally golden-coloured bronzes or golden mediaeval statues.

PB admires ancient heads with mesmerizing eyes – with their alive or half-alive character they persuade the observer of their independent existence, and with their immortality they exceed its usual limits. They seem like messengers from the afterworld realm of dark desire for the unattainable. After all, eyes are visible extremities of the brain, a supposed abide of the soul. When PB’s eyed gaze into a metaphysically absurd world, their author doesn’t feel an absolute difference from the eyes of ancient statues staring into an absolute of another nature. He cherishes them as an ideal of perfection.

Colorful heads

Acrylic on canvas, 1994-95

Colorful heads

Acrylic on canvas, 1994-95

After working on black-and-white xerox drawings and collages for an extended period, Pavel Brázda began rendering them in colour in past years. Out his black-and-white work, which has no smaller ambition than to cover the entire world theatre in all its beautiful and horrible positions, he decided to first render in colour human faces and heads.

In one of his preserved fragments Heraclitus of Ephesus says very simply: “I searched for myself.” In another: “You wouldn’t find the soul’s boundaries, however far you walked.” We all search for ourselves, whether or not we realize that. We all grope in the dark for our true form.

None of us is spared of confronting thousands forms of the human soul on that journey. Pavel Brázda draws our attention to these forms; but when he looks at our and his own “grimacing” in the process of searching and finding the infinite forms of our souls, he does so from a distance that is both ironic and sympathetic.

from the colorful heads series

digital print on canvas, 2007-2017

from the colorful heads series

digital print on canvas, 2007-2017

At the time of my big exhibition in the Prague National Gallery in 2006–7 I became intrigued by the computer, as it allowed me to process the drawn subjects much more directly and subtly. So I bought the hardware with two monitors, a bigger one for future paintings, a smaller one for technical details.